3.5 Variables transformations

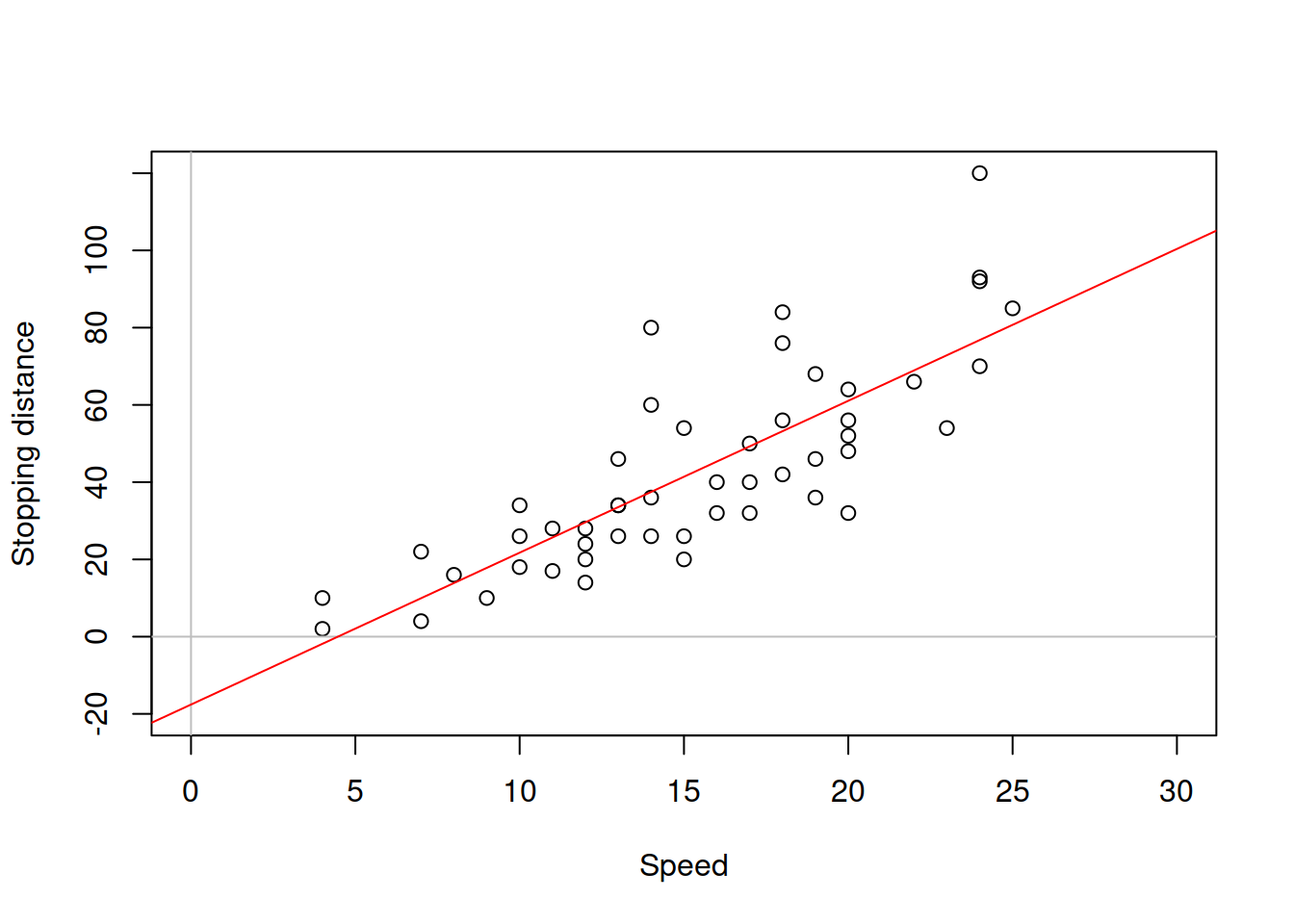

So far we have discussed linear regression models, where the response variable linearly depends on a set of explanatory variables. These models work well in many contexts, especially when the response variable is measured in high volumes (e.g. sales in thousands of units). However, in reality the relations between variables can be non-linear. Consider, for example, the stopping distance vs speed of the car, the case we have discussed in the previous sections. This sort of relation in reality is non-linear. We know from physics that the distance travelled by car is proportional to the mass of car, the squared speed and inversely proportional to the breaking force: \[\begin{equation} distance \propto \frac{mass}{2 breaking} \times speed^2. \tag{3.35} \end{equation}\] If we use the linear function instead, then we might fail in capturing the relation correctly. Here is how the linear regression looks like, when applied to the data (Figure 3.17).

Figure 3.17: Speed vs stopping distance and a linear model

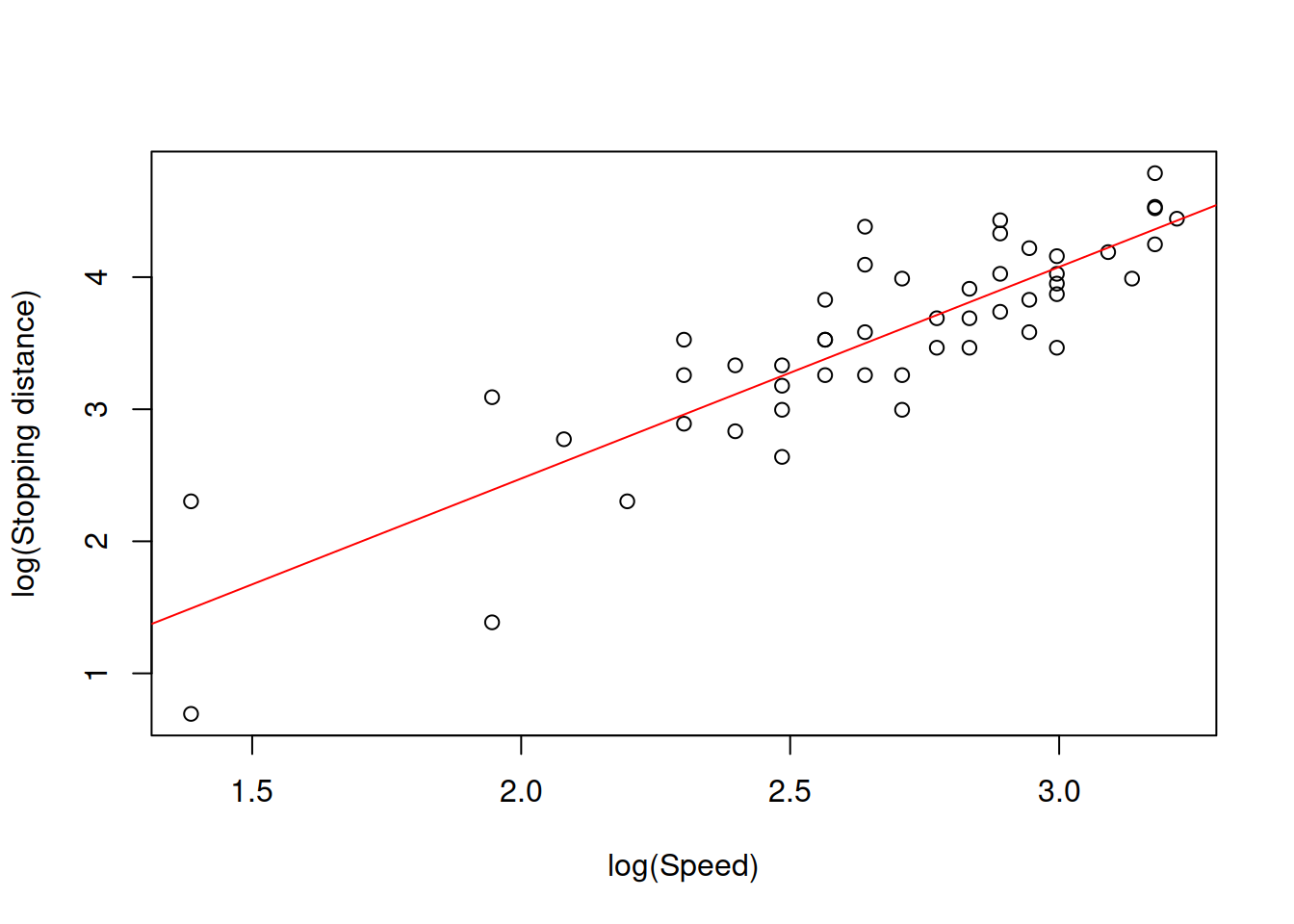

The model on the plot in Figure 3.17 is misleading, because it predicts that the stopping distance of a car, travelling with speed less than 4mph will be negative. Furthermore, the modelunderestimates the real stopping distance for cars with higher speed. If a decision is made based on this model, then it will be inevitably wrong and might potentially lead to serious repercussions in terms of road safety. Given the relation (3.35), we should consider a non-linear model. In this specific case, we should consider the model of the type: \[\begin{equation} distance = a_0 speed^{a_1} \times (1+\epsilon). \tag{3.36} \end{equation}\] The multiplication of speed by the error term is necessary, because the effect of randomness will have an increasing variability with the increase of speed: if the speed is low, then the random factors (such as road conditions, breaks condition etc) will not have a strong effect on distance, while in case of the high speed these random factors might lead either to the serious decrease or increase of distance (a car on a slippery road, stopping from 50mph will have much longer distance than the same car on a dry road). Note that I have left the parameter \(a_1\) in (eq:speedDistanceModel) and did not set it equal to two. This is done for the case we want to estimate the parameter based on the data. The problem with the model (3.36) is that it is difficult to estimate due to the non-linearity. In order to resolve this problem, we can linearise it by taking logarithms of both sides, which will lead to: \[\begin{equation} \log (distance) = \log a_0 + a_1 \log (speed) + \log(1+\epsilon). \tag{3.37} \end{equation}\] If we substituted every element with \(\log\) in (3.37) by other names (e.g. \(\log(a_0)=b_0\) and \(\log(speed)=x\)), it would be easier to see that this is a linear model, which can be estimated via OLS. This type of model is called “log-log,” reflecting that it has logarithms on both sides. Even the data will be much better behaved if we use logarithms in this situation (see Figure 3.18).

Figure 3.18: Speed vs stopping distance in logarithms

What we want to see on Figure 3.18 is the linear relation between the variables with points having fixed variance. However, in our case we can notice that the variance of the stopping distances does not seem to be stable: the variability around 2.0 is higher than the variability around 3.0. This might cause issues in the model due to violation of assumptions (see Section 3.6). For now, we acknowledge the issue but do not aim to fix it. And here how the model (3.37) can be estimated using R:

slmSpeedDistanceModel01 <- alm(log(dist)~log(speed), cars, loss="MSE")The values of parameters of this model will have a different meaning than the parameters of the linear model. Consider the example with the model above:

summary(slmSpeedDistanceModel01)## Response variable: logdist

## Distribution used in the estimation: Normal

## Loss function used in estimation: MSE

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error Lower 2.5% Upper 97.5%

## (Intercept) -0.7297 0.3758 -1.4854 0.026

## log(speed) 1.6024 0.1395 1.3218 1.883 *

##

## Error standard deviation: 0.4053

## Sample size: 50

## Number of estimated parameters: 2

## Number of degrees of freedom: 48

## Information criteria:

## AIC AICc BIC BICc

## 53.5318 53.7872 57.3559 57.8553The value of parameter for the variable log(speed) now does not represent the marginal effect of speed on distance, but rather shows the elasticity, i.e. if the speed of a car increases by 1%, the travel distance will increase on average by 1.6%.

In order to analyse the fit of the model on the original data, we would need to produce fitted values and exponentiate them. Note that in this case they would correspond to geometric rather than arithmetic means:

plot(cars, xlab="Speed", ylab="Stopping distance")

lines(cars$speed,exp(fitted(slmSpeedDistanceModel01)),col="red")

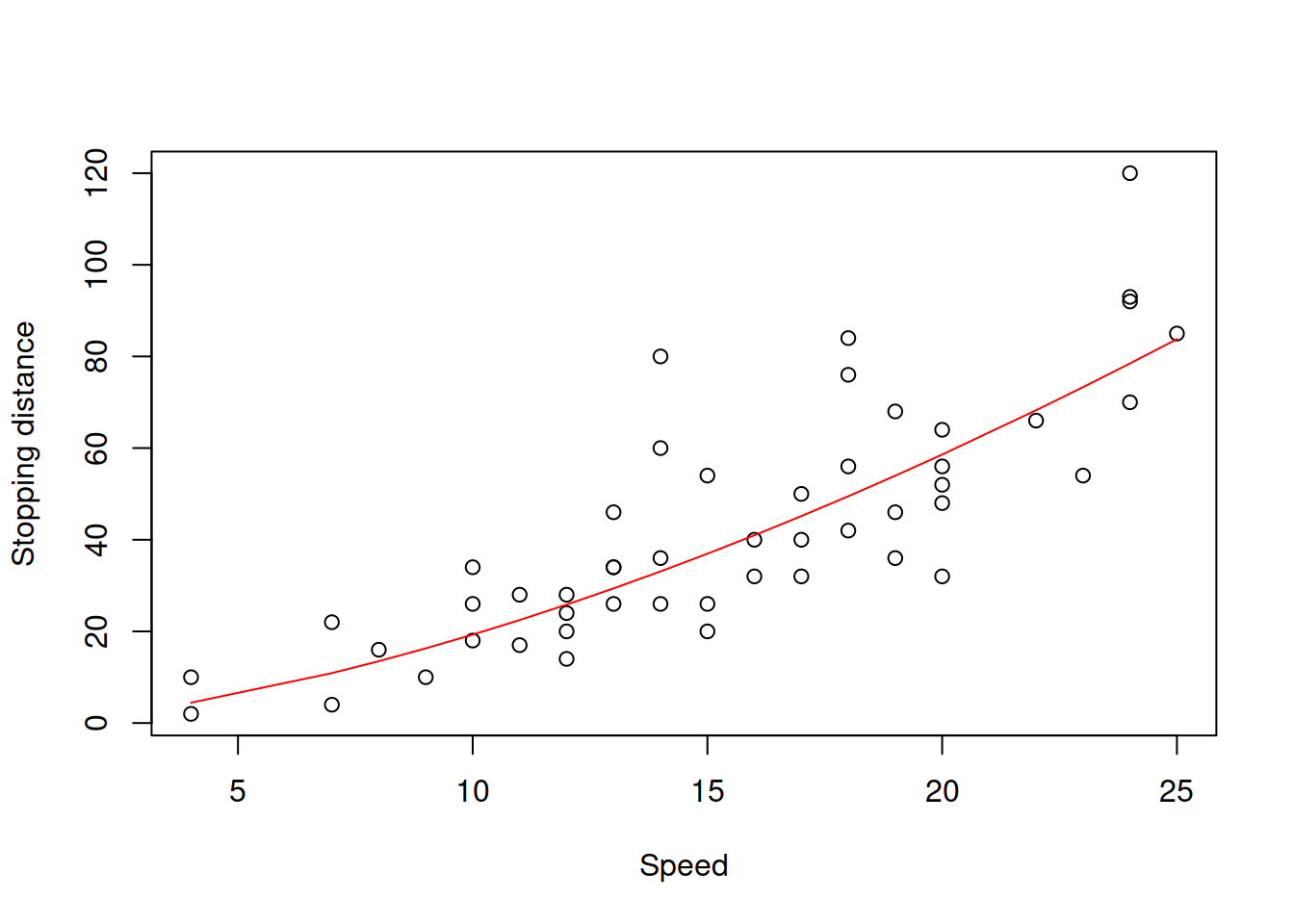

Figure 3.19: Speed vs stopping distance and the log-log model fit.

The resulting model in Figure 3.19 is the power function, which exhibits the increase in speed of change of one parameter with a linear change of another one. Note that technically speaking, the log-log model only makes sense, when the data is strictly positive. If it also contains zeroes (the speed is zero, thus the stopping distance is zero), then some other transformations might be in order. For example, we could square the speed in the model and try constructing the linear model, aligning it better with the physical model (3.35): \[\begin{equation} distance = a_0 + a_1 speed^2 + \epsilon . \tag{3.38} \end{equation}\] The issue of this model would be that the error term is additive and thus the model would assume that the variability of the error does not change with the speed, which is not realistic.

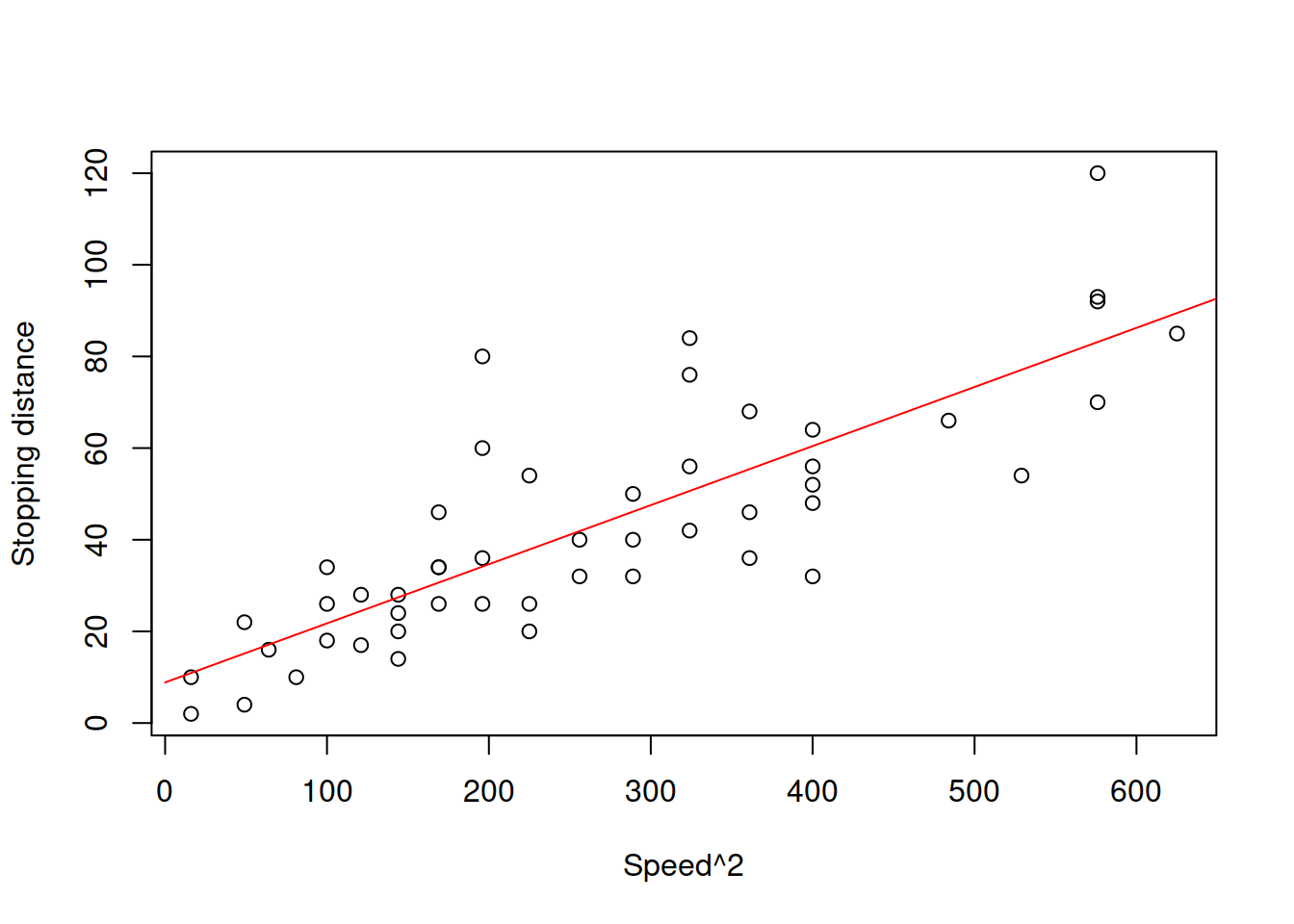

Figure 3.20: Speed squared vs stopping distance.

Figure 3.20 demonstrates the scatterplot for squared speed vs stopping distances. While we see that the relation between variables is closer to linear, the problem with variance is not resolved. If we want to estimate this model, we can use the following command in R:

slmSpeedDistanceModel02 <- alm(dist~I(speed^2), cars, loss="MSE")Note that we use I() in the formula to tell R to square the variable - it will not do the necessary transformation otherwise. Also note that in our specific case we did not include the non-transformed speed variable, because we know that the lowest distance should be, when speed is zero. But this might not be the case in other cases, so in general instead of the formula used above we should use: y~x+I(x^2). Furthermore, if we know for sure that the intercept is not needed (i.e. we know that the distance will be zero, when speed is zero), then we can remove it and estimate the model:

slmSpeedDistanceModel03 <- alm(dist~I(speed^2)-1, cars, loss="MSE")## Warning: You have asked not to include intercept in the model. We will try to

## fit the model, but this is a very naughty thing to do, and we cannot guarantee

## that it will work...alm() function will complain about the exclusion of the intercept, but it should estimate the model nonetheless. The fit of the model to the data would be similar in its shape to the one from the log-log model (see Figure 3.21).

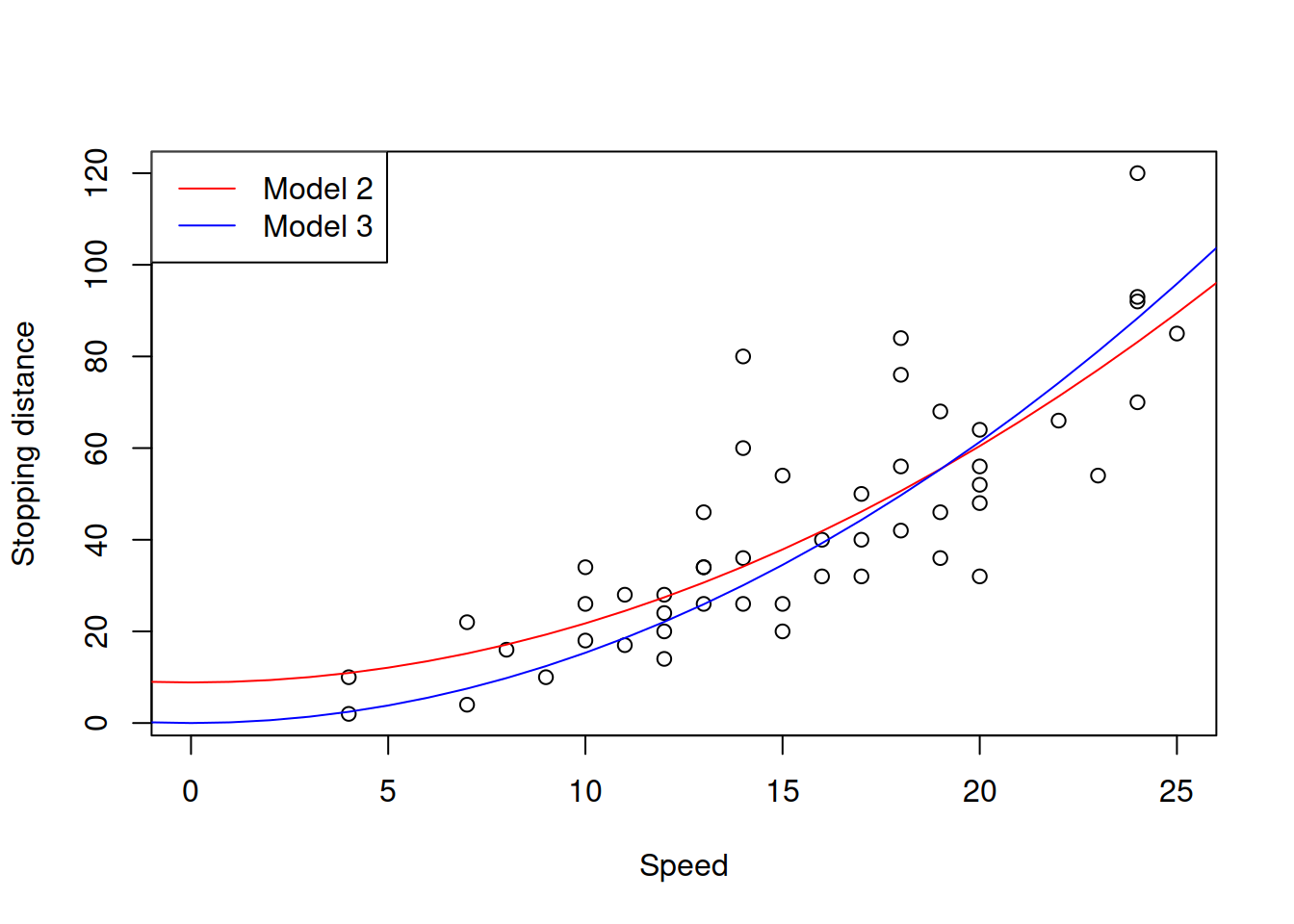

Figure 3.21: Speed squared vs stopping distance with models with speed^2.

The plot in Figure 3.21 demonstrates how the two models fit the data. The Model 2, as we see goes through the origin, which makes sense from the physical point of view. However, because of that it might fit the data worse than the Model 1 does. Still, it it better to have a more meaningful model than the one that potentially overfits the data.

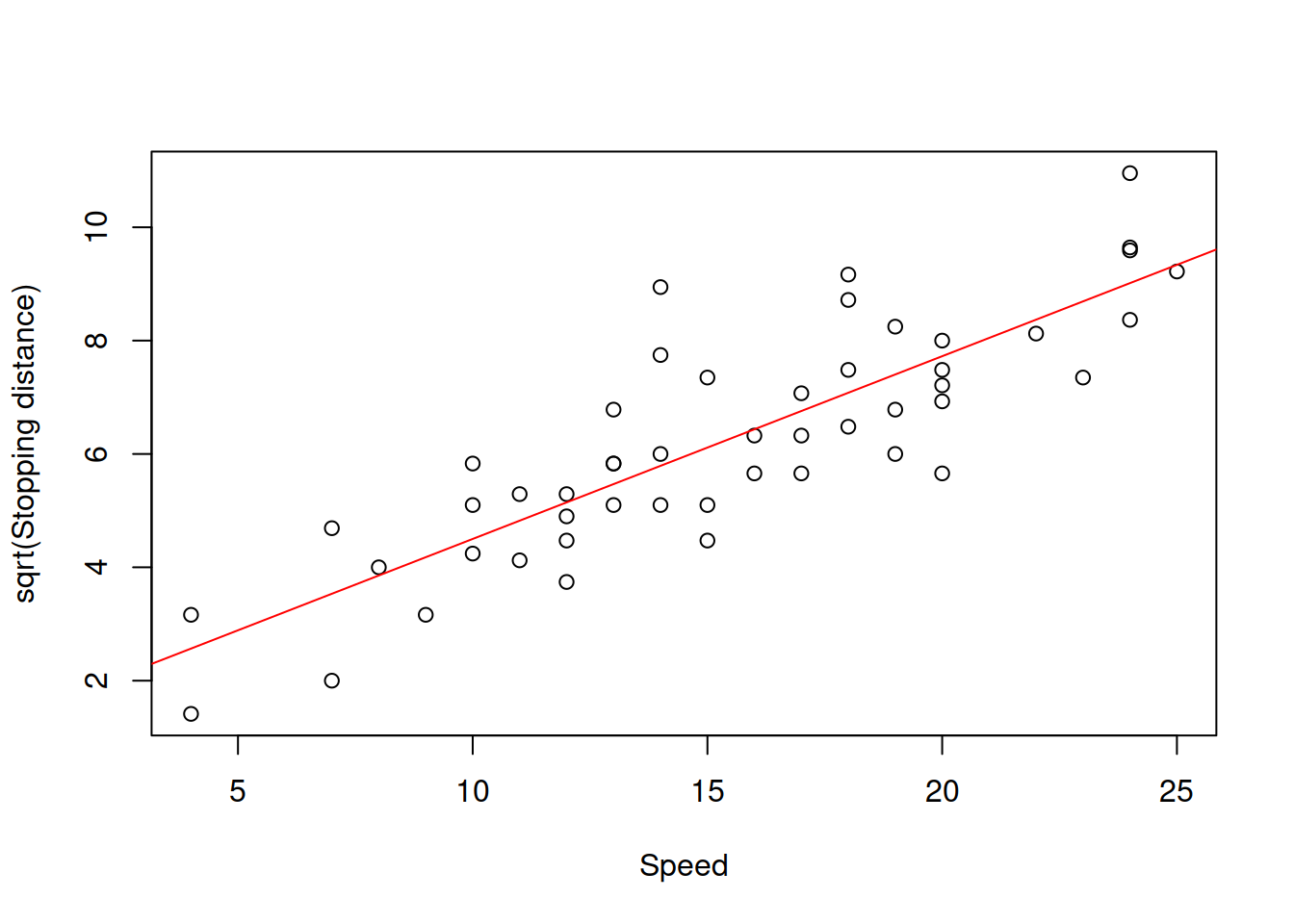

Another way to introduce the squares in the model is to take square root of distance. This would potentially align better with the physical model of stopping distance (3.35): \[\begin{equation} \sqrt{distance} = a_0 + a_1 speed + \epsilon , \tag{3.39} \end{equation}\] which will be equivalent to: \[\begin{equation} distance = (a_0 + a_1 speed + \epsilon)^2 . \tag{3.40} \end{equation}\] The good news is, the error term in this model will change with the change of speed due to the interaction effect, cause by the square of the sum in (3.40). And, similar to the previous models, the parameter \(a_0\) might not be needed. Graphically, this transformation is present on Figure 3.22.

Figure 3.22: Speed vs square root of stopping distance.

As the plot in Figure 3.22 demonstrates, the relation has become linear and the variance seems to be constant, no matter what the speed is. This means that the proposed model might be more appropriate to the data than the previous ones. This is how we can estimate this model:

slmSpeedDistanceModel04 <- alm(sqrt(dist)~speed, cars, loss="MSE")Similar to the Model 2 with squares, we will also consider the model without intercept on the grounds that if we capture the relation correctly, the zero speed should result in zero distance.

slmSpeedDistanceModel05 <- alm(sqrt(dist)~speed-1, cars, loss="MSE")## Warning: You have asked not to include intercept in the model. We will try to

## fit the model, but this is a very naughty thing to do, and we cannot guarantee

## that it will work...

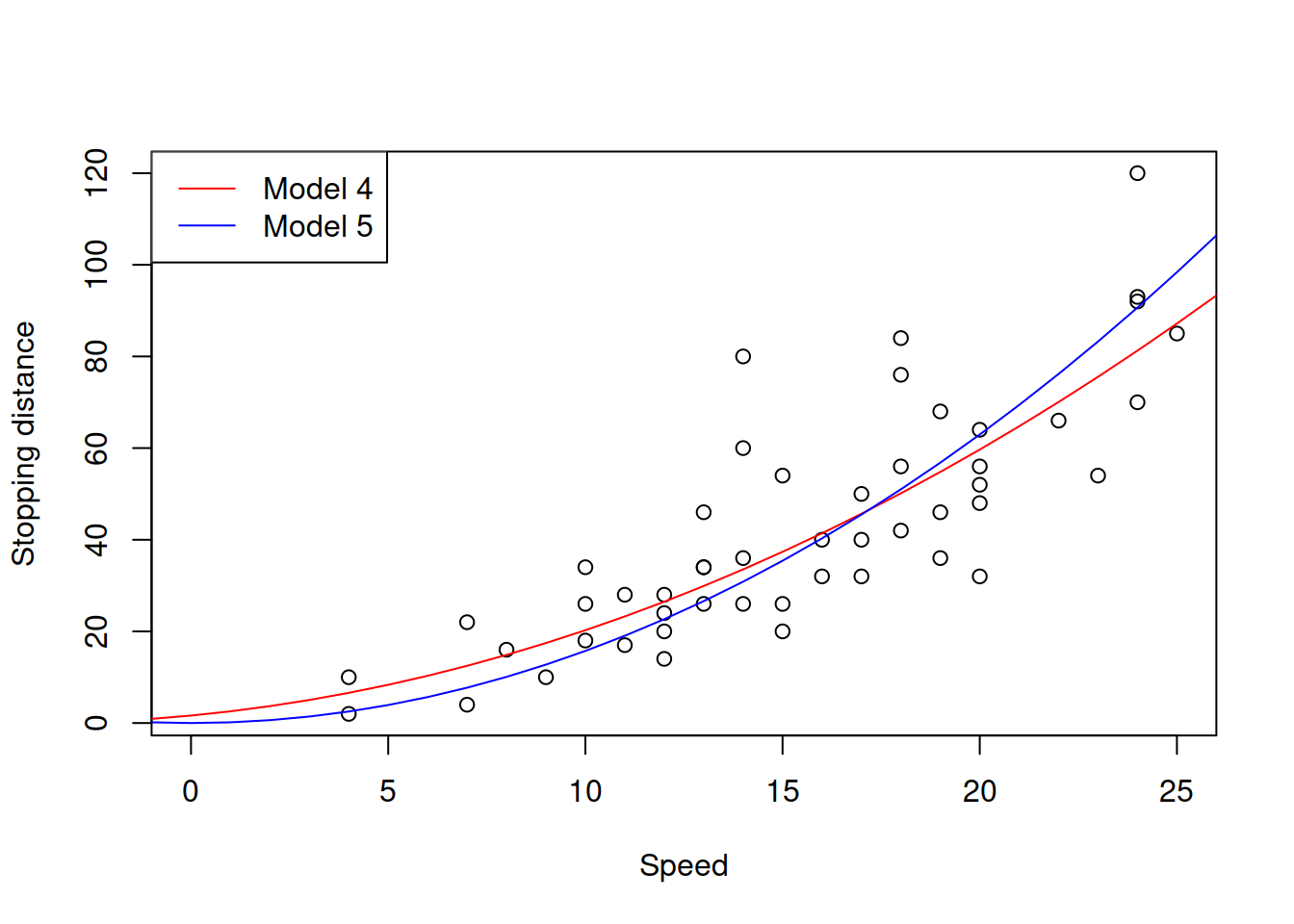

Figure 3.23: Speed squared vs stopping distance with Square Root models.

Subjectively, I would say that Model 5 is the most appropriate from all the models under consideration: it corresponds to the physical model on one hand, and has constant variance on the other one. Here is its summary:

summary(slmSpeedDistanceModel05)## Response variable: sqrtdist

## Distribution used in the estimation: Normal

## Loss function used in estimation: MSE

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error Lower 2.5% Upper 97.5%

## speed 0.3967 0.0102 0.3764 0.4171 *

##

## Error standard deviation: 1.1674

## Sample size: 50

## Number of estimated parameters: 1

## Number of degrees of freedom: 49

## Information criteria:

## AIC AICc BIC BICc

## 158.3623 158.4456 160.2743 160.4373Its parameter contains some average information about the mass of cars and their breaking forces (this is based on the formula (3.35)). The interpretation of the parameter in this model, however, is challenging. In order to get to some crude interpretation, we need to revert to maths. Model 5 can be written as: \[\begin{equation} distance = (a_1 speed + \epsilon)^2 . \tag{3.41} \end{equation}\] If we take the first derivative of distance with respect to speed, we will get: \[\begin{equation} \frac{\mathrm{d}distance}{\mathrm{d}speed} = 2 (a_1 speed + \epsilon) , \tag{3.42} \end{equation}\] which is now closer to what we need. We can say that if speed increases by 1mph, the distance will change on average by \(2 a_1 speed\). But this does not explain what the meaning of \(a_1\) in the model is. So we take the second derivative with respect to speed: \[\begin{equation} \frac{\mathrm{d}^2 distance}{\mathrm{d}^2 speed} = 2 a_1 . \tag{3.43} \end{equation}\] The meaning of the second derivative is that it shows the change of change of distance with a change of change of speed by 1. This implies a tricky interpretation of the parameter. Based on the summary above, the only thing we can conclude is that when the change of speed increases by 1mph, the change of distance will increase by 0.7934 feet. An alternative interpretation would be based on the model (3.39): with the increase of speed of car by 1mph, the square roo tof stopping distance would increase by 0.3967 square root feet. Neither of these two interpretations are very helpful, but this is the best we have for the parameter \(a_1\) in the Model 5.

3.5.1 Types of variables transformations

Having considered this case study, we can summarise the possible types of transformations of variables in regression models and what they would mean. Here, we only discuss monotonic transformations, i.e. those that guarantee that if \(x\) was increasing before transformations, it would be increasing after transformations as well.

- Linear model: \(y = a_0 + a_1 x + \epsilon\). As discussed earlier, in this model, \(a_1\) can be interpreted as a marginal effect of x on y. The typical interpretation is that with the increase of \(x\) by 1 unit, \(y\) will change on average by \(a_1\) units. In case of dummy variables, their interpretation is that the specific category of product will have a different (higher or lower) impact on \(y\) by \(a_1\) units. e.g. “sales of red mobile phones are on average higher than the sales of the blue ones by 100 units.”

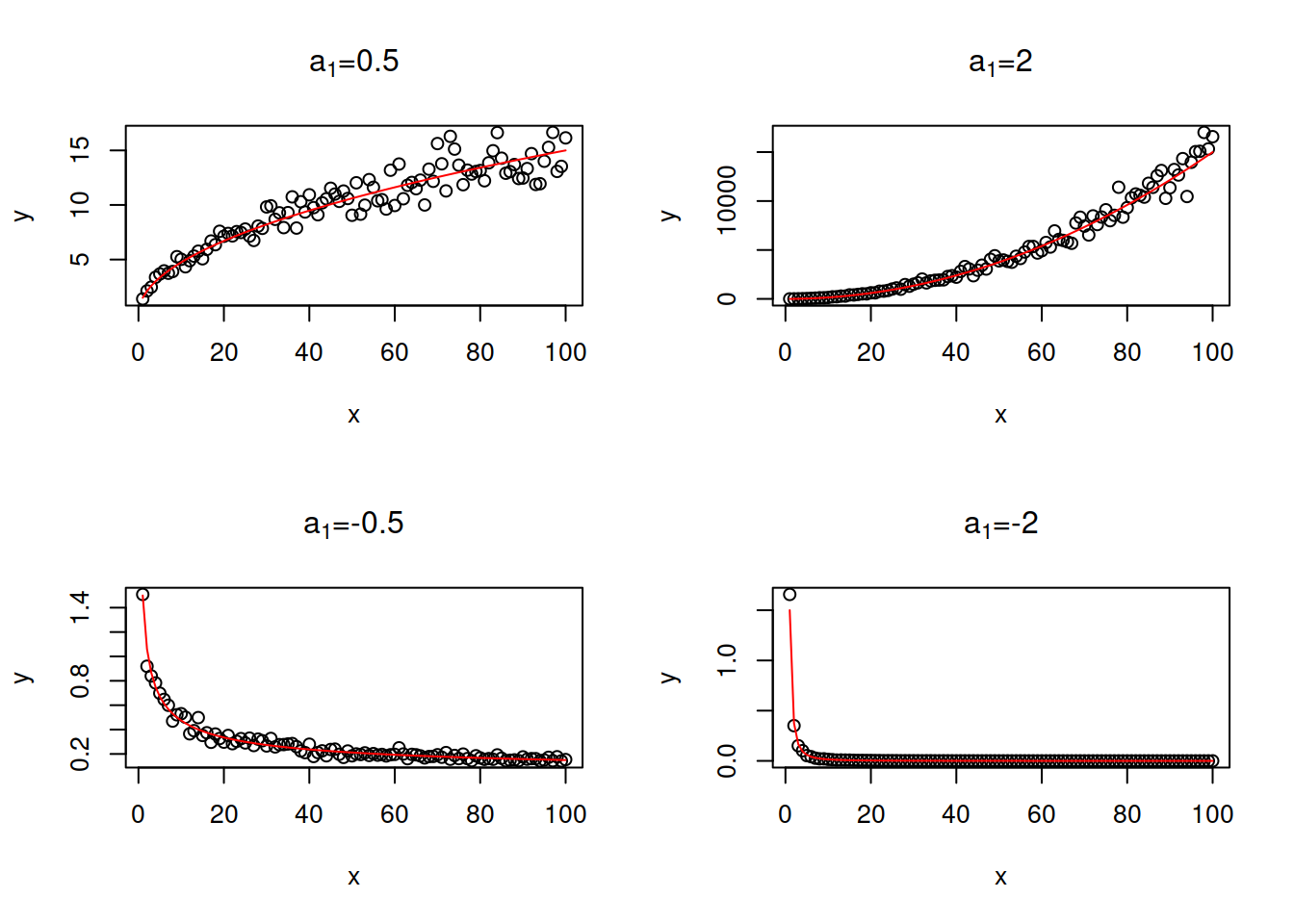

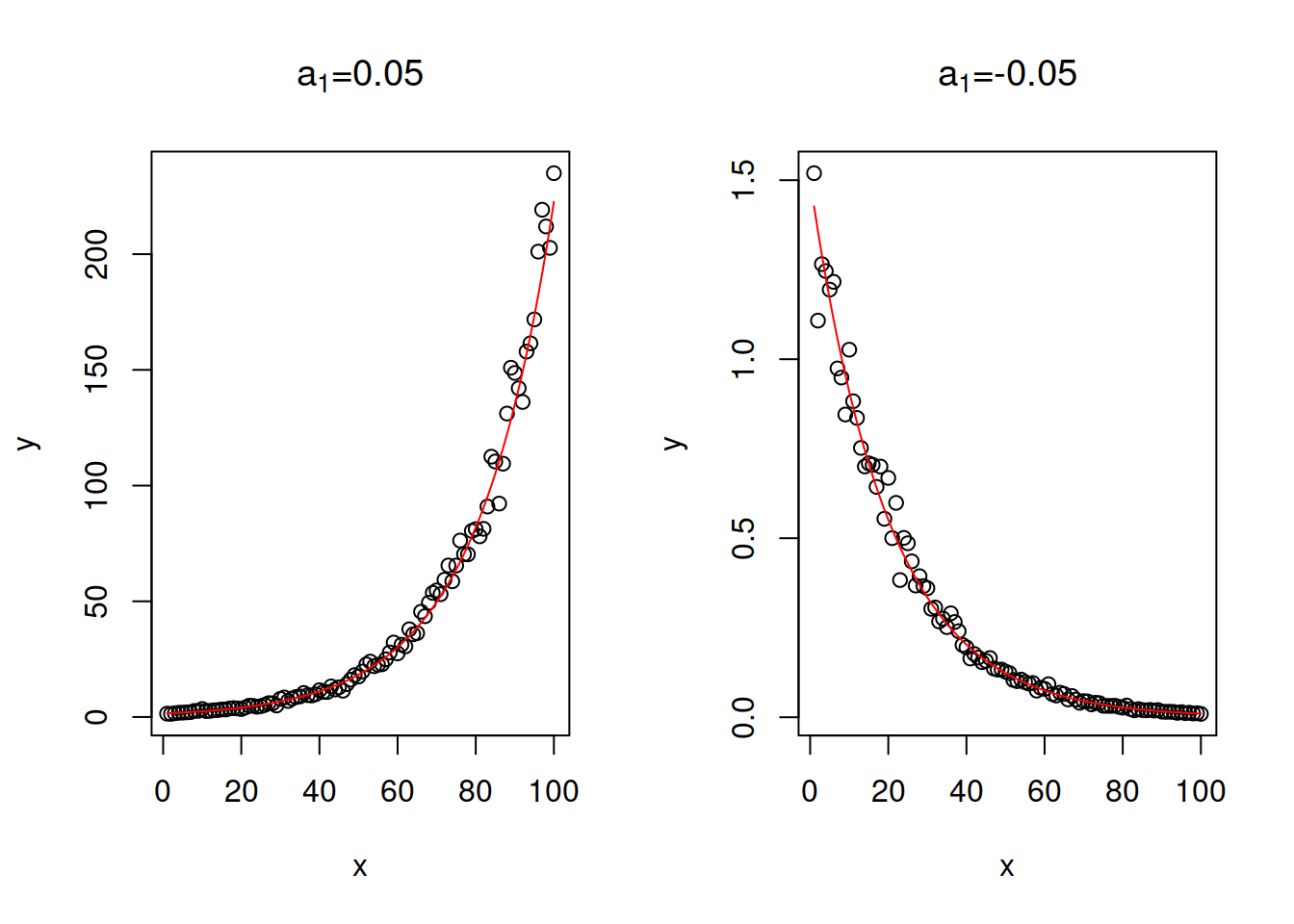

- Log-Log model, or power model or a multiplicative model: \(\log y = a_0 + a_1 \log x + \log (1+\epsilon)\). It is equivalent to \(y = a_0 x^{a_1} (1+\epsilon)\). The parameter \(a_1\) is interpreted as elasticity: If \(x\) increases by 1%, the response variable \(y\) changes on average by \(a_1\)%. Depending on the value of \(a_1\), this model can capture non-linear relations with slowing down or accelerating changes. Figure 3.24 demonstrates several examples of artificial data with different values of \(a_1\).

Figure 3.24: Examples of log-log relations with different values of elasticity parameter.

As discussed earlier, this model can only be applied to positive data. If there are zeroes in the data, then logarithm will be equal to \(-\infty\) and it would not be possible to estimate the model correctly.

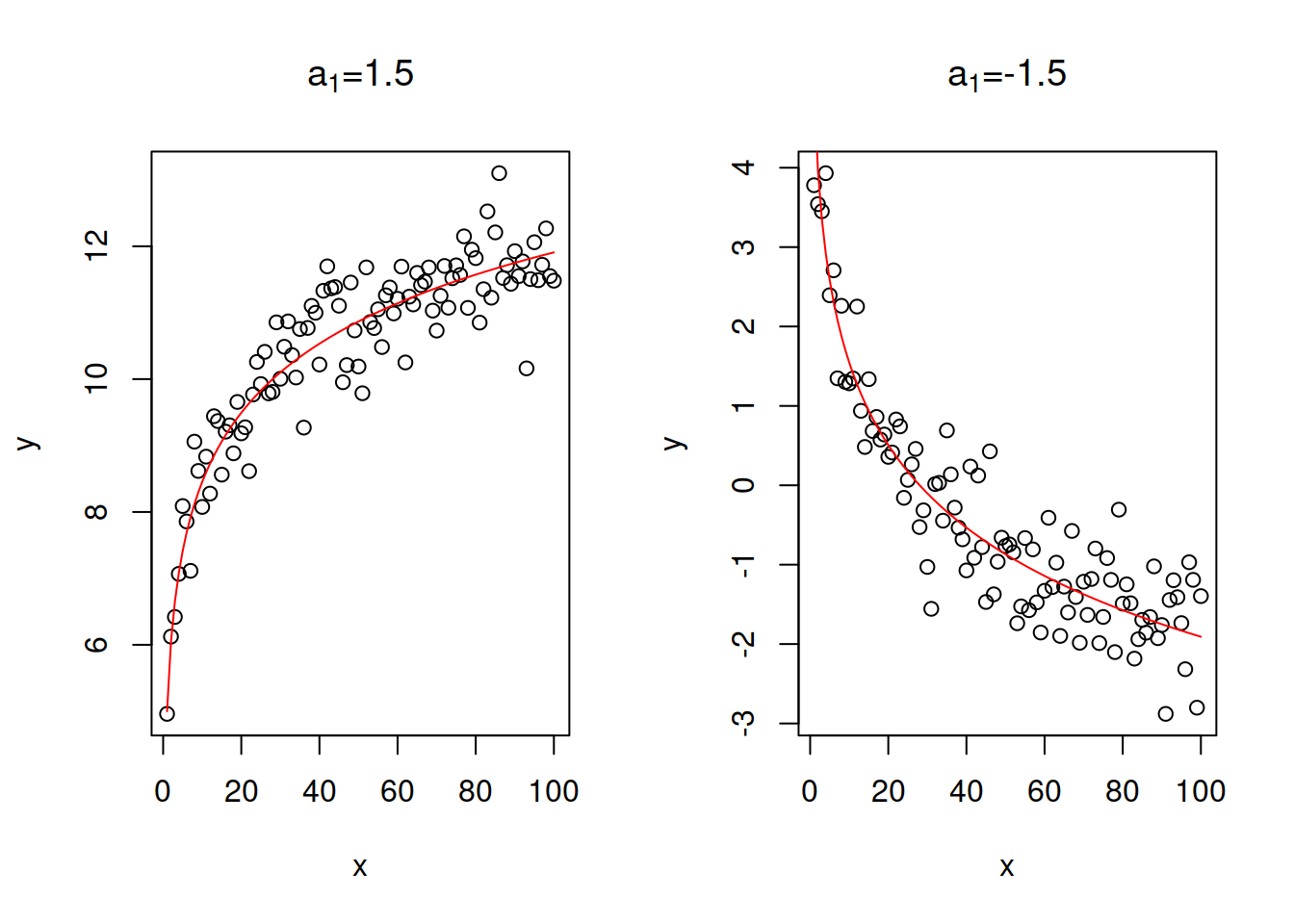

- Log-linear or exponential model: \(\log y = a_0 + a_1 x + \log (1+\epsilon)\) is equivalent to \(y = a_0 \exp(a_1 x) (1+\epsilon)\). The parameter \(a_1\) will control the change of speed of growth / decline in the model. If variable \(x\) increases by 1 unit, then the variable \(y\) will change on average by \((\exp(a_1)-1)\times 100\)%. If the value of \(a_1\) is small (roughly \(a_1 \in (-0.2, 0.2)\)), then due to one of the limits the interpretation can be simplified to: when \(x\) increases by 1 unit, the variable \(y\) will change on average by \(a_1\times 100\)%. The exponent is in general a dangerous function as it exhibits either explosive (when \(a_1 > 0\)) or implosive (when \(a_1 < 0\)) behaviour. This is shown in Figure 3.25, where the values of \(a_1\) are -0.05 and 0.05, and we can see how fast the value of \(y\) changes with the increase of \(x\).

Figure 3.25: Examples of log-linear relations with two values of slope parameter.

If \(x\) is a dummy variable, then its interpretation is slightly different: the presence of the effect \(x\) leads on average to the change of variable \(y\) by \(a_1 \times 100\)%. e.g. “sales of red laptops are on average 15% higher than sales of blue laptops.”

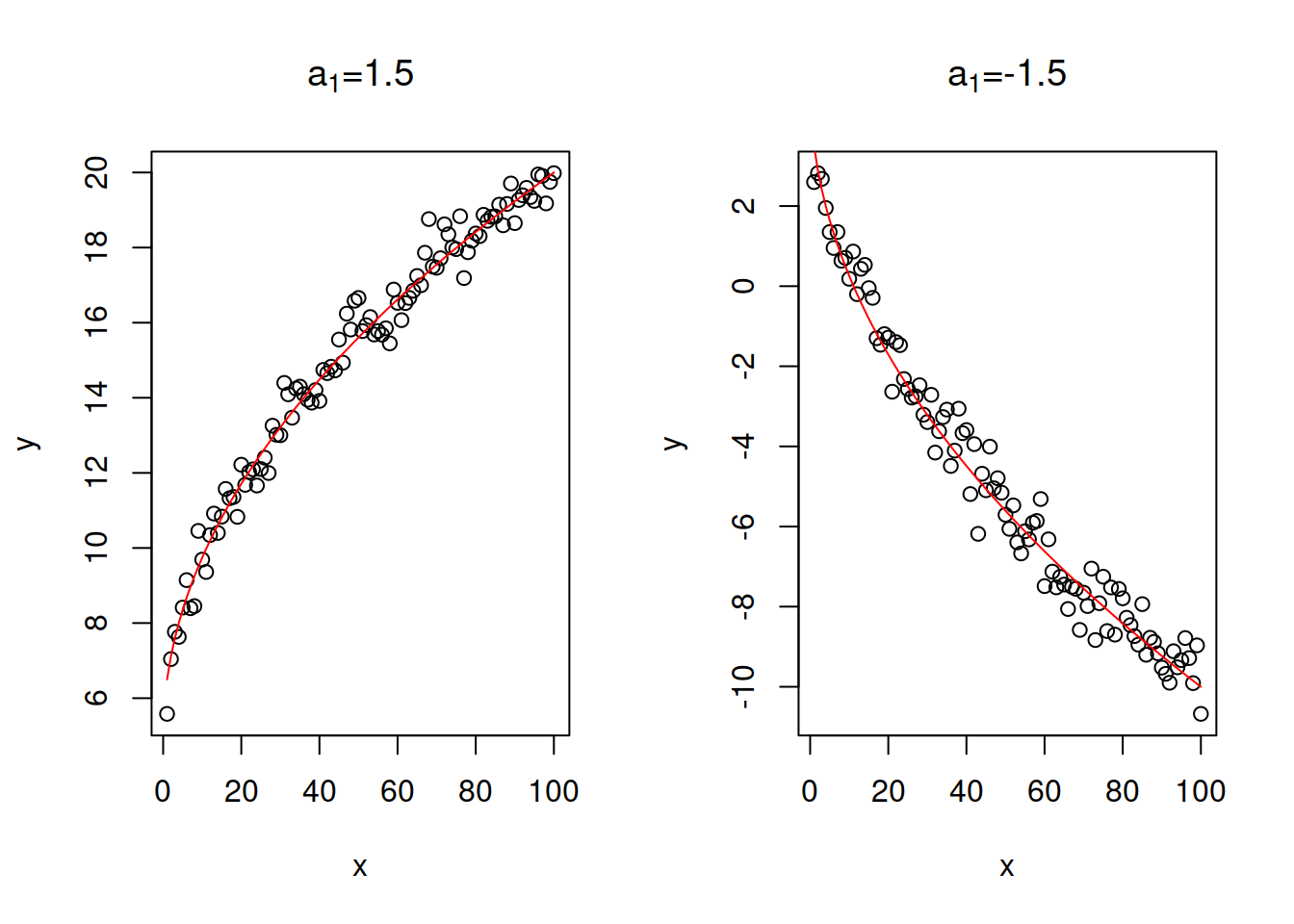

- Linear-log: \(y = a_0 + a_1 \log x + \epsilon\). This is just a logarithmic transform of explanatory variable. The parameter \(a_1\) in this case regulates the direction and speed of change. If \(x\) increases by 1%, then \(y\) will change on average by \(\frac{a_1}{100}\) units. Figure 3.26 shows two cases of relations with positive and negative slope parameters.

Figure 3.26: Examples of linear-log relations with two values of slope parameter.

The logarithmic model assumes that the increase in \(x\) always leads on average to the slow down of the value of \(y\).

- Square root: \(y = a_0 + a_1 \sqrt x + \epsilon\). The relation between \(y\) and \(x\) in this model looks similar to the on in linear-log model, but the with a lower speed of change: the square root represents the slow down in the change and might be suitable for cases of diminishing returns of scale in various real life problems. There is no specific interpretation for the parameter \(a_1\) in this model - it will show how the response variable \(y\) will change on average wih increase of square root of \(x\) by one. Figure 3.27 demonstrates square root relations for two cases, with parameters \(a_1=1.5\) and \(a_1=-1.5\).

Figure 3.27: Examples of linear - square root relations with two values of slope parameter.

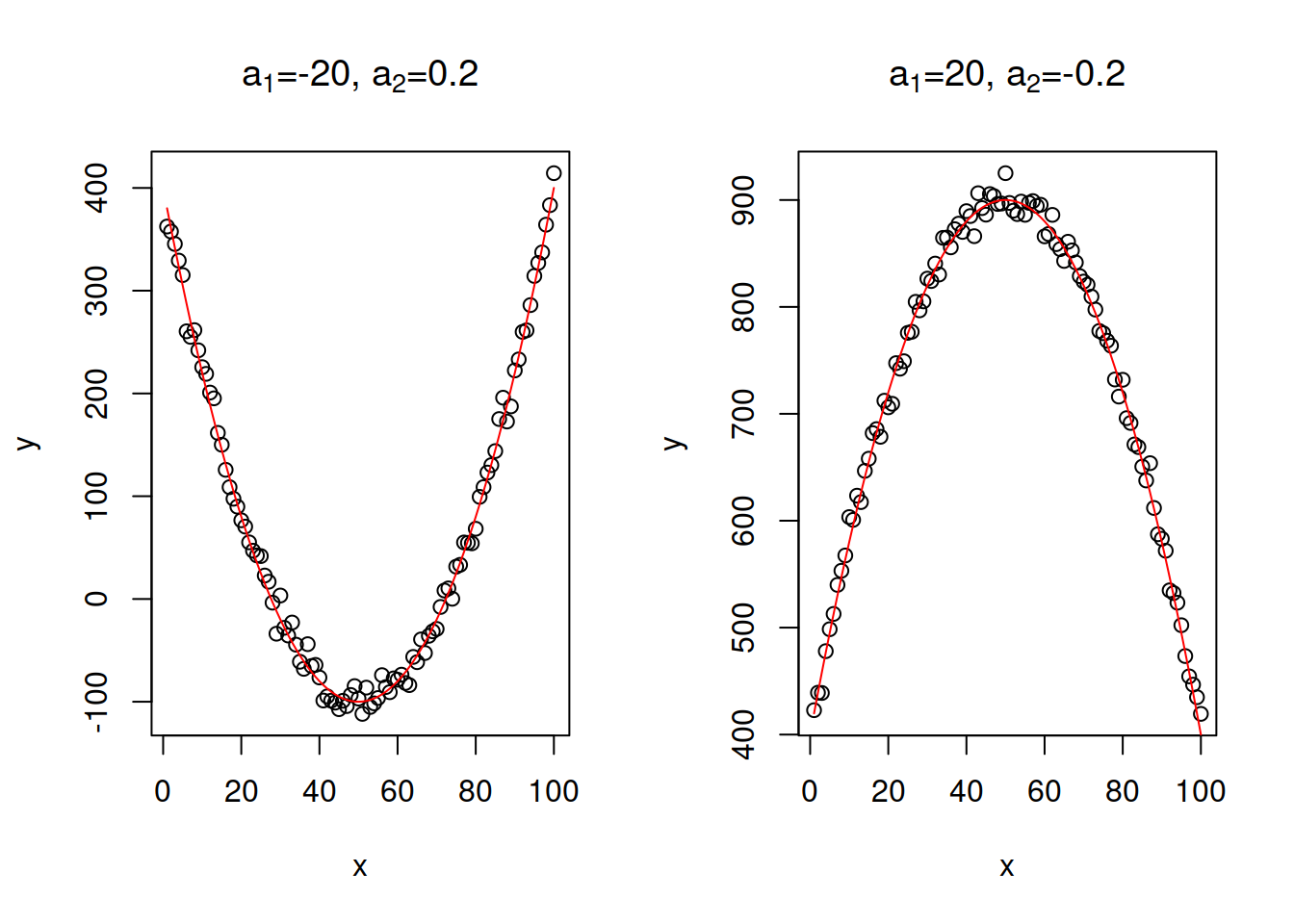

- Quadratic equation: \(y = a_0 + a_1 x + a_2 x^2 + \epsilon\). This relation demonstrates increase or decrease with an acceleration due to the present of squared \(x\). This model has an extremum (either a minimum or a maximum), when \(x=\frac{-a_1}{2 a_2}\). This means that the growth in the data will be changed by decline or vice versa with the increase of \(x\). This makes the model potentially prone to overfitting, so it needs to be used with care. Note that in general the quadratic equation should include both \(x\) and \(x^2\), unless we know that the extremum should be at the point \(x=0\) (see the example with Model 5 in the previous section). Furthrmore, this model is close to the one with square root of \(y\): \(\sqrt y = a_0 + a_1 x + \epsilon\), with the main difference being that the latter formulation assumes that the variability of the error term will change together with the change of \(x\) (so called “heteroscedasticity” effect, see Section 3.6.2). This model was used in the examples with stopping distance above. Figure 3.28 shows to classical examples: with branches of the function going down and going up.

Figure 3.28: Examples of linear-log relations with two values of slope parameter.

Polynomial: \(y = a_0 + a_1 x + a_2 x^2 + \dots \ a_k x^k + \epsilon\). This is a more general model than the quadratic one, introducing \(k\) polynomials. This is not used very often in analytics, because any data can be approximated by a high order polynomial, and because the branches of polynomial will inevitably lead to infinite increase / decrease, which is not a common tendency in practice.

Box-Cox or power transform: \(\frac{y^\lambda -1}{\lambda} = a_0 + a_1 x + \epsilon\). This type of transform can be applied to either response variable or any of explanatory variables and can be considered as something more general than linear, log-linear, quadratic and square root models. This is because with different values of \(\lambda\), the transformation would revert to one of the above. For example, with \(\lambda=1\), we end up with a linear model, just with a different intercept. If \(\lambda=0.5\), then we end up with square root, and when \(\lambda \rightarrow 0\), then the relation becomes equivalent to logarithmic. The choice of \(\lambda\) might be a challenging task on its own, however it can be estimated via likelihood. If estimated and close to either 0, 0.5, 1 or 2, then typically a respective transformation should be applied instead of Box-Cox. For example, if \(\lambda=0.49\), then taking square root might be a preferred option.

In this subsection we discussed the basic types of variables transformations on examples with simple linear regression. The more complicated models with multiple explanatory variables and complex transformations can be considered as well. However, whatever transformation is considered, it needs to be meaningful and come from the theory, not from the data. Otherwise we may overfit the data, which will lead to a variety of issues, some of which are discussed in Section 3.6.1.